The computers and robots are here – but where is the mass unemployment? An assessment after a decade of automation.

Xpert pre-release

Language selection 📢

Published on: December 5, 2025 / Updated on: December 5, 2025 – Author: Konrad Wolfenstein

The computers and robots are here – but where is the mass unemployment? An assessment after a decade of automation – Image: Xpert.Digital

Why the prophesied apocalypse didn't happen and why we still need to radically rethink things

2016: The year of great fear – What the German news magazine Spiegel predicted and what actually happened

In 2016, Der Spiegel ran one of its most influential issues with the headline: “You’re fired! How computers and robots are taking our jobs – and which professions will still be secure tomorrow.” The cover story struck a chord with a society that was observing the rise of self-learning systems, big data, and networked production facilities with growing unease. The editors compiled forecasts from technology experts, economists, and social scientists, which painted a heterogeneous picture but revealed a common trend: The labor market would fundamentally change, routine jobs would disappear, and digital disruption could lead to a wave of mass layoffs for which society was politically and structurally unprepared.

The concern wasn't new. A similar debate had already gripped West Germany in 1978, when the first wave of computerization swept through office work, accounting, and data processing. These anxieties culminated in job campaigns and company fears that digitalization could cause unemployment to skyrocket. The warnings at the time proved exaggerated, as instead of an employment collapse, a structural adjustment ensued, creating entirely new occupational fields previously unimaginable. The parallel to 2016 is obvious, as a large part of the public also predicted a dramatic upheaval back then. However, the reality we can analyze today, almost a decade later, is far more complex than the simple dichotomy of job loss versus job gain.

The figures for the years 2016 to 2024 show that automation does not tell a linear story of decline. A comprehensive study by the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) in Mannheim found that automation technologies were responsible for around 560,000 new jobs in Germany alone between 2016 and 2021. This figure may seem modest given the 45 million employees subject to social security contributions, but it refutes the thesis of massive job losses due to robots and artificial intelligence. The development varied across sectors: While the energy and water supply sector recorded job growth of 3.3 percent, and the electronics and automotive industries also benefited with 3.2 percent growth, the construction industry lost around 4.9 percent of its jobs. The education, health, and social sectors were also not immune to automation-related efficiency gains that enabled staff reductions.

Suitable for:

- Computers in 1978, now AI and robotics: progress makes people unemployed – why this 200-year-old prophecy keeps failing.

From Luddism to the AI revolution: Why fear of technology is as old as progress itself

Warnings about job destruction through technology are not a 21st-century invention. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, when Henry Ford put the first moving assembly line into operation at his Highland Park factory in 1913, critics predicted the dehumanization of work and the erosion of skilled trades. Ford not only revolutionized automobile production but also sparked a societal debate that resonates to this day. Workers became cogs in a machine, their tasks so fragmented that any individual craftsmanship seemed obsolete. Unemployment did not initially rise, but the quality of work changed fundamentally. This historical analogy is instructive because it shows that technological revolutions always have two sides: a destructive one that replaces old structures and skills, and a constructive one that opens up new economic possibilities.

The Luddites in early 19th-century England, who destroyed mechanical looms because they saw their craft livelihoods threatened, are the archetypal example of a society overwhelmed by the consequences of technological change. Yet even this radical movement could not halt industrialization. Instead, new fields of employment emerged in the iron and steel industry, transportation, construction, and later, the service sector. The lesson is clear: technology never replaces work per se, but rather changes the way work is organized. The fear surrounding 2016 was therefore an echo of historical patterns that repeat themselves whenever a new wave of technology shakes up established orders.

Germany experienced this transformation particularly intensely due to its industrial structure. The automotive industry, long the backbone of the German economy, invested heavily in robotics and AI-supported production systems. The result was not the predicted job losses, but rather a shift in workforce from purely manufacturing tasks to higher-value activities in programming, maintenance, and process optimization. While the number of people directly employed in production decreased, overall employment within companies increased or remained stable because new business areas emerged in data analytics, the development of driver assistance systems, and digital customer service.

Luddism refers to an early labor movement, primarily originating in England at the beginning of the 19th century, which opposed the social consequences of industrialization, particularly the use of new machinery in the textile industry, sometimes resorting to violent means. Today, the term is often used more broadly to describe a fundamental or militant skepticism towards technology, for example in the context of so-called Neo-Luddism.

Historical Luddism arose roughly between 1811 and 1814 in English regions such as Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and Lancashire, where textile workers experienced massive wage cuts, job losses, and impoverishment due to mechanized spinning mills and looms. The so-called Luddites deliberately destroyed machines and factories to protest the deteriorating living conditions and new, perceived as unjust, economic relationships; the state responded with military force, executions, and deportations to Australia.

The movement took its name from the legendary, presumably fictional figure "Ned Ludd" (also known as King or General Ludd), who was considered a symbolic leader and defender of traditional artisans' rights. His name served as a collective pseudonym in protest letters and became the point of reference for the entire Luddite movement, which is therefore known as Luddism.

For a long time, Luddites were portrayed as blind enemies of technology who fought against machines per se; more recent historical research, however, emphasizes that they primarily opposed wage dumping, the erosion of rights, and new power structures, and that they attacked machines very selectively. The destruction of machines was thus less a result of irrational hostility to progress, but rather a symbolic and economic form of exerting pressure on certain entrepreneurs.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, "Luddite" has often been used pejoratively for groups or individuals critical of technology who fundamentally question modern technologies such as digitalization, genetic engineering, nuclear technology, or nanotechnology, sometimes resorting to violence. Today, "Neo-Luddism" encompasses a wide range of movements—from radical technophobes to movements critical of growth and progress—that draw on the tradition of the early Luddites.

The hard results after eight years: 560,000 new jobs instead of mass layoffs.

Empirical evidence from recent years refutes the thesis of a comprehensive employment collapse due to digitalization and robotics. The ZEW study shows that automation in Germany had a net positive effect on the labor market between 2016 and 2021. The 560,000 newly created jobs did not occur by chance, but were concentrated in regions and sectors that invested in digitalization early on. Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, the two states with the highest levels of automation, simultaneously recorded the lowest unemployment rates and the most severe shortage of skilled workers. This seems paradoxical, but can be explained economically: Automation increases productivity, reduces costs, and enables companies to tap into new market segments, which in turn require personnel.

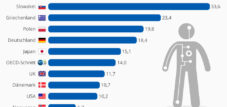

The World Economic Forum offers a global perspective that places Germany within the context of international developments. Its forecasts for the period 2018 to 2027 reveal a complex dynamic: while 75 million jobs worldwide could be lost to automation by 2025, 133 million new positions will simultaneously be created. The net effect is an increase of 58 million jobs. For Germany, the models predict a similarly positive scenario: 1.6 million old jobs will be replaced by 2.3 million new ones, resulting in a net increase of 700,000 positions. These figures are politically significant because they contradict the popular narrative of mass job losses due to technology.

But the figures mask a more complex reality. The jobs that are created generally require higher qualifications than those that disappear. The McKinsey Global Institute study predicts that up to three million jobs in Germany could be affected by changes by 2030, representing seven percent of total employment. Office jobs in administration, customer service, and sales are particularly affected, accounting for 54 percent of all job changes caused by AI. The shift is clear: While accountants, legal assistants, and cashiers once represented the stability of the German labor market, today it is data analysts, AI developers, and IT specialists who are in demand.

Industries in transition: Where robots are really destroying jobs – and where they are creating them

The sectoral analysis reveals a polarization with far-reaching societal consequences. The manufacturing industry, particularly the automotive and electrical sectors, underwent profound transformation. The number of industrial robots in Germany rose steadily, reaching over 260,000 units in 2023. In theory, each of these robots replaced four to six human workers in purely handling and assembly tasks. In reality, around 275,000 full-time jobs were lost in the manufacturing sector. However, at the same time, 490,000 new jobs were created in sectors outside of traditional manufacturing, primarily in IT services, software development, and digital infrastructure.

The energy and water supply sector benefited most from technological advances. Job growth of 3.3 percent in this sector resulted not from expansive demand, but from the need to operate complex smart grid systems, decentralized energy generation, and AI-powered grid control. These new requirements created highly skilled positions that did not previously exist. A similar pattern emerged in the electronics industry, where job growth of 3.2 percent was directly linked to the development of IoT devices, sensor systems, and chip design.

In contrast, the construction industry saw a 4.9 percent job loss. This was not solely due to automation, but rather a combination of efficiency gains through construction software, modular building methods, and a shortage of skilled workers that hampered growth. The education, health, and social sectors presented a mixed picture: While nurses and educators were in high demand due to demographic shifts, digital assistants, telemedicine systems, and AI-supported administrative processes enabled staff reductions in support functions.

The situation is particularly critical in the banking and insurance sectors. The number of tellers and bank employees has fallen significantly, while at the same time the demand for IT specialists in cybersecurity, data analysis, and digital customer service has exploded. The sector experienced a net loss of jobs, which was, however, offset by increased productivity and new digital products. The result is a skills gap that only 46 percent of German workers can bridge, as they possess the necessary digital skills to meet these new demands.

🎯🎯🎯 Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, five-fold expertise in a comprehensive service package | BD, R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization

Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, fivefold expertise in a comprehensive service package | R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization - Image: Xpert.Digital

Xpert.Digital has in-depth knowledge of various industries. This allows us to develop tailor-made strategies that are tailored precisely to the requirements and challenges of your specific market segment. By continually analyzing market trends and following industry developments, we can act with foresight and offer innovative solutions. Through the combination of experience and knowledge, we generate added value and give our customers a decisive competitive advantage.

More about it here:

Robotics and AI skills gap instead of job killer: How 22 million employees must reinvent themselves for the AI era

Robotics and AI skills gap instead of job killer: How 22 million employees must reinvent themselves for the AI era – Image: Xpert.Digital

Germany in the grip of transformation: Between skills shortage and skills gap

The German labor market reality in 2025 is characterized by a paradoxical situation: record-low unemployment coupled with a dramatic shortage of skilled workers and massive skills gaps within the population. According to a survey by the ifo Institute, 27 percent of German companies expect AI to lead to job losses in the next five years. However, the German Economic Institute (IW) reports that the share of AI-related job postings in Germany has stagnated at a meager 1.5 percent since 2022. This discrepancy is alarming: companies fear being displaced but are not investing in developing AI expertise.

The Bertelsmann Foundation recently warned that Germany could fall behind in leveraging the economic opportunities of AI. The study emphasizes that AI could increase overall economic productivity in Germany by 16 percent if it were implemented nationwide. However, many companies, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), are hesitant to invest in new technologies and the associated retraining of their workforce. The result is a vicious cycle: without investment, productivity remains low; without productivity gains, there is a lack of capital for investments in human capital.

Demographic trends are exacerbating the situation. The number of academically qualified individuals is growing steadily due to higher education, but the labor market cannot fully absorb this increasing supply. At the same time, the supply of mid-level skilled workers is declining faster than demand, leading to shortages that can only be partially alleviated by automation. The healthcare and nursing sector is a prime example: demographic change is driving up the demand for nursing staff, while automation technologies such as care robots or digital assistance systems are only slowly being implemented and are hardly leading to any reduction in personnel.

Suitable for:

Humans as a bottleneck: Why the labor market isn't collapsing, but could tip over.

The central finding of current labor market research is this: the bottleneck is not technology, but people. The IAB (Institute for Employment Research) modeled a scenario in which Industry 4.0 will not lead to any significant change in the total number of employees by 2030. In summary, Industry 4.0 is neither a job creator nor a job killer. However, dramatic shifts are taking place beneath the surface. A total of 490,000 jobs could be lost in traditional sectors, while 430,000 new ones could be created. The net figure may appear balanced, but the people affected are not the same. The assembly worker in the automotive industry will not automatically become a data analyst at an IT service provider.

Skills requirements are shifting dramatically. The McKinsey Global Institute predicts that the core competencies of 44 percent of workers will change within the next five years. By 2030, almost 40 percent of the skills required for a job will be obsolete. Demand for technical skills will increase by 25 percent in Europe, while social and emotional skills will gain 12 percent in importance. Workers are partially aware of this development: 59 percent expect AI to reduce the need for human labor. However, only 46 percent possess the necessary skills to thrive in this new environment.

This gap between requirements and skills is the real risk. Labor market policy in Germany has so far focused on securing jobs, not on ensuring employability. While the federal government's Qualification Initiative Act offers financial incentives, allowing the Federal Employment Agency to cover up to 100 percent of further training costs and 75 percent of wages during training, uptake remains low. Many companies fear losing qualified employees to competitors after further training and are therefore hesitant to invest.

The major retraining trap: 44 percent of employees have to reinvent themselves.

The ability to adapt professionally is becoming a crucial competitive factor. The World Economic Forum estimates that 54 percent of all workers will require significant retraining and further education to keep pace with the demands of automation. In Germany, this equates to approximately 22 million people. However, the actual implementation of these reskilling and upskilling programs is lagging. Only 60 percent of companies actively invest in training programs for their employees, and even these investments are often concentrated on highly skilled individuals in key positions.

The result is an increasing polarization of the labor market. Highly skilled workers with digital skills receive wage premiums of up to 56 percent, while low-skilled workers slip into precarious employment. The regional dimension of this divide is also evident: Metropolitan regions like Munich, Berlin, and Hamburg, with their dynamic IT and service markets, attract skilled workers, while rural regions with an industrial structure struggle to cope with structural change. The share of high-paid jobs in Germany could rise by 1.8 percentage points, while the share of low-paid jobs could fall by 1.4 percentage points.

This development is not inevitable, but it requires proactive political action. With the Qualification Offensive Act, the German Federal Government has created a framework that provides financial support for in-company training. However, experience from recent years shows that incentives alone are insufficient. Companies must be legally obligated to invest a certain percentage of their workforce resources in training, similar to the practices in some Scandinavian countries. Furthermore, the content of training programs must be more closely aligned with the actual needs of the digital economy, focusing on practical AI applications, data analysis, and digital process optimization.

From horse economics to prompt engineering: Learning from history

History teaches us that the biggest losers in technological revolutions are not those whose jobs disappear, but those who refuse to adapt. When motorization replaced the horse-based economy of the 19th century, coachmen and carters lost their livelihoods. But at the same time, new professions emerged, such as bus drivers, train drivers, and later, professional truck drivers. The transformation took a generation, but was ultimately successful because education systems and vocational training adapted.

The current transformation is faster and more profound. While the rise of the automobile took decades to reach its full potential, AI is spreading in just a few years. The half-life of technological knowledge is shortening dramatically. A computer science degree from 2015 is now partially obsolete because the underlying technologies have fundamentally changed. The ability to learn and retrain quickly is becoming more important than any specific technical expertise.

This requires a radical realignment of the education system. Dual vocational training, long the backbone of the German economy, must be digitized and modularized. Instead of fixed three-year apprenticeships, we need flexible qualification pathways supplemented by certifications every few years. The first signs are visible: Some large companies like Siemens or Bosch offer internal academies that continuously update employees. But these initiatives remain privileged islands in a sea of stagnation.

Suitable for:

The next decade will be different – and tougher.

Forecasts for 2025 to 2030 indicate an acceleration of change. The World Economic Forum expects 170 million new jobs worldwide, while 92 million jobs will be displaced, resulting in a net increase of 78 million. However, these figures mask a qualitative intensification. The new jobs are emerging in fields that don't even exist today. Prompt engineering, AI training, digital ethics, cybersecurity, and quantum computing are just a few examples of professional fields that will gain massive importance in five years.

Germany faces a dilemma. On the one hand, the country has a massive shortage of skilled workers, exacerbated by demographic trends. On the other hand, AI adoption in companies is stagnating. The share of AI-related job postings has remained at 1.5 percent since 2022, while other countries like the US and China show significantly higher figures. This hesitancy is costing Germany competitiveness. A study by Bertelsmann and the German Economic Institute (IW) shows that AI could increase productivity in Germany by 16 percent if it were implemented nationwide. However, uncertainty surrounding regulatory frameworks, data protection, and high investment costs is hindering its widespread adoption.

The political response must encompass several levels. First, an active industrial policy is needed that specifically promotes the use of AI in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) through subsidies, consulting services, and testing environments. Second, the education system must be radically reformed towards lifelong learning, modular qualifications, and greater integration of digital technologies into all vocational training programs. Third, social security systems must be adapted to cushion transition phases in which employees move between traditional and new occupational fields.

The big question posed by Der Spiegel in 2016 cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. Computers and robots haven't taken our jobs, but they have changed the work we do and radically transformed the skills we need. The challenge of the next decade is not to preserve jobs, but to ensure people's employability. If we rise to this challenge, automation can lead to increased prosperity for everyone. If we fail to do so, we risk a social divide that will shake the foundations of our social order. The robots are here, and they're here to stay. Now it's up to us to shape the human side of this transformation.

EU/DE Data Security | Integration of an independent and cross-data source AI platform for all business needs

Ki-Gamechanger: The most flexible AI platform-tailor-made solutions that reduce costs, improve their decisions and increase efficiency

Independent AI platform: Integrates all relevant company data sources

- Fast AI integration: tailor-made AI solutions for companies in hours or days instead of months

- Flexible infrastructure: cloud-based or hosting in your own data center (Germany, Europe, free choice of location)

- Highest data security: Use in law firms is the safe evidence

- Use across a wide variety of company data sources

- Choice of your own or various AI models (DE, EU, USA, CN)

More about it here:

Advice - planning - implementation

I would be happy to serve as your personal advisor.

contact me under Wolfenstein ∂ Xpert.digital

call me under +49 89 674 804 (Munich)