Skilled worker shortage? The mini-job trap as a systemic brake on the German economy

Xpert pre-release

Language selection 📢

Published on: November 12, 2025 / Updated on: November 12, 2025 – Author: Konrad Wolfenstein

Hidden potential: Why 4.5 million mini-jobbers could be the answer to our skilled worker shortage

The invisible trap for women: Why the mini-job often leads directly to poverty in old age – Why a radical reform now seems unavoidable

For millions of people in Germany, it's seen as a flexible way to earn extra income or an uncomplicated entry into the workforce. But behind the facade of the popular mini-job lies an economic burden that is increasingly becoming a systemic obstacle for the German economy. While business associations emphasize the advantages for companies and employees, numerous studies prove the opposite: clinging to the current mini-job model is costing Germany dearly, weakening the social security system, and exacerbating the skilled worker shortage.

The scale of this structural problem is enormous: around 7 million people work in marginal employment, and for approximately 4.5 million of them, it is their only source of income. Particularly in sectors like retail and hospitality, the mini-job has become deeply entrenched and demonstrably displaces regular, full-time jobs with social security contributions. This development has serious and multifaceted consequences: it leads to billions of euros in annual losses in social security funds, blocks productivity gains, and wastes valuable human capital – especially that of women, for whom the mini-job often becomes a dead end in their careers, with the risk of poverty in old age.

The recent debate, sparked by a proposal from the CDU, brings into focus the pressing question: Can Germany still afford this luxury while hundreds of thousands of skilled worker positions remain unfilled? This article lays bare the economic connections, exposes specious arguments, and demonstrates why a fundamental reform of marginal employment is not a mere social policy footnote, but an economic policy necessity for the future viability of Germany as a business location.

Suitable for:

When labor market policy becomes an economic burden: Why clinging to the status quo is proving costly for Germany.

The debate surrounding the future of marginal employment in Germany reveals fundamental design flaws in the German labor market that extend far beyond social policy considerations. Those who defend the existing mini-job model either overlook the macroeconomic context and the detrimental effects on German economic performance, or they are acting out of opportunistic calculation. The recent debate, triggered by the initiative of CDU Member of Parliament Stefan Nacke, exposes a critical weakness in the German economic model that has been causing considerable damage for years.

The quantitative dimension of a structural problem

The raw figures paint a clear picture of the scale of the mini-job phenomenon in Germany. As of the second quarter of 2025, a total of 7.023 million people were registered with the Mini-Job Center in marginal employment, of whom 6.764 million were in the commercial sector and 258,742 in private households. Of these mini-jobbers, approximately 4.4 to 4.5 million people pursue this activity as their sole source of income, which corresponds to about 11.4 percent of all employees. This means that a significant portion of the working population is trapped in an employment relationship that was originally intended as a temporary solution or supplementary income.

The distribution of these marginal employment relationships is by no means uniform. In the retail sector, of 3.1 million employees, around 800,000 work in mini-jobs, which corresponds to a share of approximately 26 percent. The trade and maintenance and repair of motor vehicles sector leads the statistics with 1.159 million mini-jobbers, followed by the hospitality industry with 946,647 marginally employed workers. The situation is particularly problematic in small businesses with fewer than ten employees, where almost 40 percent of the workforce works in mini-jobs, while in large companies it is only ten percent.

The displacement of productive jobs as economic damage

Perhaps the most serious negative consequence of the mini-job system lies in the systematic displacement of regular, full-time employment subject to social security contributions. The Institute for Employment Research has demonstrated in several comprehensive studies that mini-jobs do not complement regular employment, but rather replace it. Specifically, in small businesses with fewer than ten employees, an additional mini-job replaces, on average, half a full-time position subject to social security contributions.

Extrapolated to the entire economy, mini-jobs in small businesses alone have displaced approximately 500,000 jobs subject to social security contributions. This displacement is not a theoretical construct but can be empirically proven. When the earnings threshold for mini-jobs was raised from €325 to €400 in 2003, the number of mini-jobbers jumped from around four million to over six million. This increase was not accompanied by a corresponding expansion of overall employment, but rather by the conversion of regular employment relationships into marginal employment.

The retail, hospitality, and healthcare and social services sectors are particularly affected. In these sectors, there is a clear correlation between the growth in mini-jobs and the decline in regular jobs. This development is highly problematic from an economic perspective, as regular jobs are typically associated with higher productivity, better utilization of skills, and higher wages than mini-jobs.

The fiscal drain on social security systems

The fiscal impact of the mini-job regulations places a considerable burden on public budgets and social security systems. While employees subject to social security contributions pay around 40 percent of their gross wages into social security together with their employers, this figure is only 28 percent for mini-jobs. The employer pays a flat-rate contribution of 13 percent for health insurance and 15 percent for pension insurance. The mini-jobber is exempt from health, long-term care, and unemployment insurance and pays only 3.6 percent into pension insurance, unless an exemption has been applied for.

The revenue shortfalls of social security already amounted to over three billion euros annually in 2014. Given the increased number of marginally employed people and the higher earnings thresholds, these shortfalls are likely to be significantly higher today. These structural revenue losses weaken the financial base of social security at a time when demographic change is already putting the systems under pressure.

Added to this is the burden of basic income support. Since those in marginal employment (minijobs) are not entitled to unemployment benefits, they fall directly into basic income support if they lose their jobs. This became particularly evident during the COVID-19 crisis, when 870,000 people in marginal employment lost their jobs. The probability of job loss is about twelve times higher for those in marginal employment than for those in jobs subject to social security contributions. This extreme vulnerability to crises leads to volatile burdens on municipal and federal budgets.

The wasted added value and blocked productivity

Perhaps the most costly economic consequence of the mini-job system lies in the wasted growth potential and the stunted productivity development. Model calculations by the Bertelsmann Foundation impressively demonstrate the economic opportunities squandered by the existing system. A reform to abolish mini-jobs while simultaneously reducing social security contributions for lower income groups could increase the gross domestic product by €7.2 billion by 2030 and create 165,000 additional jobs.

These growth potentials arise through several mechanisms. First, the transition from mini-jobs to regular part-time or full-time employment typically leads to an increase in labor productivity and wages. Mini-jobs are often associated with unskilled work that is below the employees' skill level. From an economic perspective, a qualified professional with completed vocational training who remains permanently in a mini-job is wasting their human capital.

Secondly, the mini-job system hinders both the expansion of working hours and an increase in the labor supply. A significant obstacle arises at the earnings threshold of €556, as exceeding this amount triggers a sharp increase in social security contributions of approximately 20 percent. This penalizes overtime and creates disincentives. Employees and employers have a shared interest in remaining at this limit, even if more working hours would be economically beneficial and desired by the employee.

Suitable for:

- Apprenticeship or university studies: A myth that a career is only possible through university? Decision-making processes, opportunities, and career prospects

The gender-specific dimension of the mini-job trap

The issue of mini-jobs has a pronounced gender-specific component that extends far beyond equality concerns and has significant macroeconomic implications. Around 65 percent of those exclusively employed in marginal employment are women. Among those primarily employed in mini-jobs, the proportion of women is even higher, at two-thirds. This overrepresentation of women is not accidental, but rather structurally determined.

Minijobs act as a career dead end, especially for women after periods of family leave. The supposed advantages of flexible working hours and low hours are offset by significant disadvantages. Even women with qualified vocational training are no longer perceived as skilled professionals after prolonged employment in a minijob. Their negotiating position in subsequent job interviews is considerably weaker than that of comparable applicants.

Only about 40 percent of women who work exclusively in mini-jobs manage to return to employment subject to social security contributions. Of those who do make this transition, nearly two-thirds receive a net income of less than €1,000 in their new job. This is even true for over 28 percent of full-time employees. These income losses continue into old age and lead to systematic poverty among elderly women.

From an economic perspective, this structural disadvantage for women wastes enormous potential skilled workers. Given the skilled labor shortage in many sectors, employing qualified women in unskilled jobs is a luxury Germany cannot afford. Studies show that better pay and working conditions in personal social service professions, as well as converting mini-jobs into jobs with social security contributions, would not only combat gender inequality but also alleviate the skilled labor shortage.

Our EU and Germany expertise in business development, sales and marketing

Industry focus: B2B, digitalization (from AI to XR), mechanical engineering, logistics, renewable energies and industry

More about it here:

A topic hub with insights and expertise:

- Knowledge platform on the global and regional economy, innovation and industry-specific trends

- Collection of analyses, impulses and background information from our focus areas

- A place for expertise and information on current developments in business and technology

- Topic hub for companies that want to learn about markets, digitalization and industry innovations

Reform instead of specious arguments: This is how Germany could rethink mini-jobs

The economic costs of the skills shortage

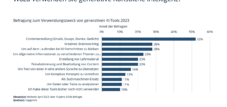

The connection between the mini-job system and the skilled worker shortage in Germany is more direct than it might initially appear. Various studies estimate the economic costs of this shortage at between 49 and 86 billion euros annually. In 2023, 570,000 jobs remained unfilled. At the same time, over four million people work exclusively in mini-jobs, many of them with qualified vocational training.

Minijobs significantly deprive the regular labor market of potential workers. They create incentives to remain in marginal employment instead of increasing working hours or accepting a regular position. For mothers with children, a minijob is often the only way to reconcile work and family life because childcare infrastructure is lacking or regular part-time jobs with a living wage are scarce.

The high turnover rate in mini-jobs (63 percent compared to 29 percent for regular employees) incurs additional costs for recruitment and training. Companies invest less in the further training of mini-jobbers because these employment relationships are viewed as temporary. This prevents productivity gains through experience and further exacerbates the skilled worker shortage.

Suitable for:

The opportunistic calculations of the defenders

The vehement defense of the mini-job system by associations like the German Retail Federation and the German Hotel and Restaurant Association (Dehoga) is economically understandable, even if it is problematic from a macroeconomic perspective. For individual sectors and businesses, mini-jobs offer short-term economic advantages. The lower overall labor costs compared to regular employment, the flexibility in scheduling, and the uncomplicated administration make mini-jobs attractive to employers.

Stefan Genth, CEO of the German Retail Federation, argues that the 800,000 part-time workers in the retail sector are essential for managing industry-specific peak times at midday and in the evening. If this workforce were to disappear suddenly, it could not be compensated for. In the worst-case scenario, retailers would no longer be able to offer their usual level of service at all times and across the entire country.

Sandra Warden, Managing Director of the German Hotel and Restaurant Association (Dehoga), warns that past attacks on mini-jobs have led to the elimination of such jobs or a shift to undeclared work. She argues that mini-jobs are indispensable to the hospitality industry. Gitta Connemann, CDU leader of the SME sector and Federal Government Commissioner for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, also emphasizes that small and medium-sized enterprises and their employees need mini-jobs, finding the model attractive and straightforward.

This argument, however, overlooks the overall economic costs of the system. What appears rational at the individual company level leads to suboptimal results for the economy as a whole. The lower personnel costs for mini-jobbers are more than offset by lower productivity, higher employee turnover, and the macroeconomic costs of lost social security contributions. The flexibility advantages for employers are bought at the price of the inflexibility the system creates for employees.

Suitable for:

The use of undeclared work as a specious argument

The argument put forward by associations that abolishing mini-jobs would lead to a shift towards undeclared work does not stand up to closer scrutiny. In fact, the mini-job system itself can be used to conceal undeclared work by having only a small portion of the work performed legally as a mini-job, thus allowing those involved to effectively evade inspections.

Internationally, there are numerous examples of countries without a comparable mini-job system that nevertheless do not experience rampant undeclared work. The crucial factor is not the existence of marginal employment relationships with special status, but rather a functioning tax system, effective controls, and attractive legal employment alternatives.

Experience with minimum wage increases in Germany shows that the feared massive shift to undeclared work has not materialized. Employees value the social security and legal clarity of regular employment, even if their net pay is reduced by taxes and social security contributions. The claim that mini-jobs are necessary to prevent undeclared work is therefore a specious argument that obscures the true motives of those who defend them.

International Perspectives and Reform Models

A look beyond Germany's borders reveals that the German mini-job system is an international anomaly. Most OECD countries do not have a comparable special regulation for marginal employment. Instead, they rely on other instruments to support low incomes and create work incentives.

The British Working Tax Credit system combines minimum wages with tax-based wage subsidies embedded in the income tax system. The Working Tax Credit promotes employment of 16 hours or more per week and creates genuine work incentives through degressive withdrawal rates. The US Earned Income Tax Credit system is considered one of the most successful anti-poverty programs worldwide. It reaches 23 million families with a total of $64 billion and rewards work with a tax credit that initially increases with rising earned income, then remains constant, and finally is gradually reduced.

The French Revenu de Solidarité Active demonstrates how combined wages can work. When transitioning into employment, only 38 percent of social assistance is deducted instead of 100 percent, creating strong work incentives. All these systems avoid creating a parallel world of work with its own set of rules and incentive structures.

Reform options for Germany

A future-proof reform of the German system of marginal employment would have to combine several elements. First, the special status of mini-jobs should be ended and replaced by a sliding transition zone ranging from zero euros to at least 1,800 euros per month. Within this zone, social security contributions would increase linearly from zero to approximately 20 percent, thus eliminating the sharp drop-off at the current mini-job threshold.

A negative income tax system modeled on the American Earned Income Tax Credit could directly support low-income earners without creating the job-damaging incentives of the current system. It could be implemented using the existing infrastructure of tax offices, thus avoiding the creation of new bureaucracy.

The dynamic adjustment of earnings thresholds to the minimum wage, as introduced in 2022, should be maintained. This prevents structural problems from arising due to minimum wage increases. In addition, mandatory training programs for those in marginal employment should be introduced to ensure that this form of employment actually serves as a stepping stone to regular employment.

Companies that transition mini-jobbers into jobs subject to social security contributions could be rewarded with transfer bonuses or tax incentives. This would create a direct financial incentive to further develop mini-jobbers and open up prospects for them in the regular labor market.

The fiscal implications of a reform

Model calculations show that a comprehensive reform would initially incur fiscal costs, but could become self-financing in the medium term. By 2041, the additional revenue for the public sector would exceed the fiscal costs of the reform. Social security system revenues would increase due to more contributors, while expenditures for basic income support and other transfer payments could decrease.

A reform that abolishes the special status of mini-jobs and simultaneously extends the sliding scale to €1,800 could reduce unemployment by up to 92,600 people in the long term. Both part-time and full-time employment would increase significantly, while marginal employment would decline sharply. Overall, an increase in employment of approximately 68,900 full-time equivalent positions could be expected.

The Bertelsmann study projects GDP growth of €7.2 billion by 2030 and 165,000 additional jobs. These growth effects will result from higher productivity, better allocation of human capital, and reduced friction in the labor market. Low-skilled workers and single parents would particularly benefit from such a reform.

The political economy of the blockade

The question of why, despite the clear economic findings, no fundamental reform of the mini-job system has taken place, leads to the heart of political economy. The concentrated interests of employers in sectors with a high proportion of mini-jobs stand in contrast to the diffuse interests of the overall economy and the employees affected. Associations such as the German Retail Federation and the German Hotel and Restaurant Association (Dehoga) can mobilize their members and exert pressure on politicians.

On the employee side, there is no comparable representation for those in marginal employment (minijobs). Unions have limited reach of this group, as many minijobbers are not unionized. Those affected often see short-term advantages in the system, since they receive the same net pay as gross pay and are covered by their spouse's health insurance. The long-term disadvantages, such as poverty in old age and limited career opportunities, are underestimated or ignored.

Political parties shy away from the issue because there are no easy solutions and any reform would create losers. However, the current debate shows that even within the CDU/CSU, the realization is increasingly taking hold that the system needs reform. Stefan Nacke's initiative, supported by the SPD, the Greens, the Left Party, and the Verdi trade union, could open a window for change.

The need for a paradigm shift

Economic analysis clearly shows that the German mini-job system does more harm than good. It displaces productive jobs, weakens social security, wastes human capital, stifles economic growth, and perpetuates gender inequality. The short-term business advantages for individual sectors are more than offset by the long-term macroeconomic costs.

A sustainable labor market system for Germany must organize work in a way that is worthwhile for employees, offers social security, and opens up career development opportunities. At the same time, it must provide companies with the necessary flexibility and minimize bureaucracy. International experience shows that this is possible without a mini-job system.

Reforming the regulations governing mini-jobs is not a minor social policy issue, but an economic necessity. Germany cannot afford to continue keeping millions of people in a form of employment that was originally intended as an exception but has now become the rule. The economic connections are clear, and studies have demonstrated the beneficial effect of reform on economic performance. Anyone who nevertheless clings to the German mini-job model is acting either out of ignorance or out of opportunistic calculation at the expense of the overall economy and future generations.

Your global marketing and business development partner

☑️ Our business language is English or German

☑️ NEW: Correspondence in your national language!

I would be happy to serve you and my team as a personal advisor.

You can contact me by filling out the contact form or simply call me on +49 89 89 674 804 (Munich) . My email address is: wolfenstein ∂ xpert.digital

I'm looking forward to our joint project.

☑️ SME support in strategy, consulting, planning and implementation

☑️ Creation or realignment of the digital strategy and digitalization

☑️ Expansion and optimization of international sales processes

☑️ Global & Digital B2B trading platforms

☑️ Pioneer Business Development / Marketing / PR / Trade Fairs

🎯🎯🎯 Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, five-fold expertise in a comprehensive service package | BD, R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization

Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, fivefold expertise in a comprehensive service package | R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization - Image: Xpert.Digital

Xpert.Digital has in-depth knowledge of various industries. This allows us to develop tailor-made strategies that are tailored precisely to the requirements and challenges of your specific market segment. By continually analyzing market trends and following industry developments, we can act with foresight and offer innovative solutions. Through the combination of experience and knowledge, we generate added value and give our customers a decisive competitive advantage.

More about it here: