The German deep-tech paradox: Germany faces the biggest economic policy puzzle in its history – Image: Xpert.Digital

Industrial innovations “Made in Germany” – profits in the USA: The absurd gift to the competition

World champions in invention, losers in sales: The quiet demise of Germany's deep-tech hope

How can a nation with one of the world's densest and most excellent research landscapes simultaneously struggle so much to generate global prosperity from this knowledge? We find ourselves in the midst of a "deep-tech paradox." In the laboratories of the Max Planck and Fraunhofer Institutes, the technological breakthroughs of tomorrow are conceived—from artificial intelligence to quantum technology. But in Germany, the path from the laboratory to the global market resembles an obstacle course, at the end of which there is often not a global breakthrough "Made in Germany," but rather a sale to US investors.

The diagnosis is painful, but clear: While Germany invests billions in basic research, the system fails at the crucial moment of scaling. Bureaucratic hurdles that paralyze startups for years and a dramatic lack of growth capital drive the most promising companies and talent out of the country. We finance the seeds, but others reap the harvest – primarily the USA. Given a projected market potential of eight trillion euros in the deep tech sector, this is far more than an industrial policy failure; it is a threat to the future sovereignty and competitiveness of the German economy.

With the new High-Tech Agenda and instruments like the Future Fund, policymakers are now attempting to counteract this trend and turn things around. But is the pace of these measures sufficient to keep up in the global race? The following article analyzes the structural deficits between research excellence and stagnation in scaling, examines the phenomenon of brain drain, and shows which strategic decisions are now necessary so that Germany's brightest minds not only conduct research here, but also secure the prosperity of tomorrow.

Suitable for:

- Stuttgart 21 – a symbol of political project failure and a lack of understanding of economic realities

Bureaucratic madness instead of world market leadership: How forms are destroying our future prosperity

Between research excellence and scaling stagnation: Why the brightest minds leave before they increase prosperity

Germany's technological future viability is at a critical turning point. With the High-Tech Agenda adopted in July 2025, the Federal Government has created a programmatic framework that recognizes the strategic importance of key technologies for value creation, competitiveness, and sovereignty. Thomas Koenen, Head of the Digitalization and Innovation Department at the Federation of German Industries (BDI), observes in this context that the Federal Government has apparently recognized that innovation is no longer optional. This assessment gets to the heart of an economic debate that extends far beyond day-to-day political trends and raises fundamental questions about the competitive positioning of German industry in the global technology race.

At first glance, the starting point for deep-tech innovations in Germany appears quite promising. Germany boasts a world-class research ecosystem, which holds leading international positions, particularly in basic research. The Max Planck Society, the Fraunhofer Society, and other non-university research institutions form a dense network of scientific excellence that serves as an indispensable foundation for the development of deep-tech technologies. The combination of cutting-edge basic research and application-oriented research represents a comparative advantage found in this form in only a few economies. With the application-oriented research of the Fraunhofer Institutes and other institutions, Germany is also fundamentally well-positioned in the area of technology transfer.

The economic dimension of this potential is considerable. Deep-tech technologies encompass fields such as artificial intelligence, AI-based robotics, quantum technologies, and biotechnology, with a focus on mRNA-based therapies, cell therapies, and gene therapies. Studies predict a global value creation potential of up to eight trillion euros for these technology fields by 2030. This presents substantial opportunities for Germany if it succeeds in consistently translating its existing research strengths into marketable products and services.

The attractiveness of deep-tech technologies for businesses lies in their fundamental characteristics. Successes in this field are based on the principle that they are difficult to achieve, but equally difficult to replicate. These high barriers to entry create sustainable competitive advantages for companies that achieve technological breakthroughs. Large corporations and numerous industrial startups in Germany, ready to invest, recognize this potential and are generally prepared to mobilize the necessary resources.

Suitable for:

- Typically German because we need a bureaucracy relief law? The current status of the economy and renewable energies such as PV

The gap between potential and realization

Despite these favorable conditions, a detailed analysis reveals significant structural deficiencies in the German innovation ecosystem. The central problem lies not in a lack of ideas or scientific expertise, but in the mechanisms that bridge the gap between basic research and market penetration. In complex technological fields like deep tech, with their inherent high levels of uncertainty, government support is of paramount importance. Numerous other countries have recognized this and support their research institutions and industries with appropriate programs and resources.

In Germany, however, a serious problem with the pace of government funding processes is evident. Application procedures for public funding are often far too complex and time-consuming. This bureaucratic complexity hits small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) particularly hard. SMEs, which traditionally form the backbone of the German innovation landscape, have neither the time nor the personnel resources for lengthy bureaucratic processes. Consequently, frustration among SMEs is pronounced, especially since technological development cycles in deep-tech sectors demand a speed that seems hardly compatible with current funding procedures.

The time dimension of this problem is considerable. In some cases, years pass before a company actually receives the requested funding. This timeframe is starkly disproportionate to the dynamic development cycles in technology markets, where competitive positions can shift fundamentally within a few months. The example of the Federal Agency for Disruptive Innovation shows that the so-called "time to money" can be significantly shortened.

The first evaluation of SPRIND, founded in 2019, was positive and confirmed that the agency has succeeded in establishing agile and flexible structures to provide targeted, rapid, and precisely tailored support for projects with disruptive innovation potential. In 2024, SPRIND had approximately €229 million at its disposal, of which around €137 million was allocated to start-ups and approximately €79 million to research projects. To date, the agency has supported 72 projects at universities, non-university research institutions, or by private individuals, with 32 of these projects being transferred into companies. This track record underscores the potential of leaner funding structures but cannot disguise the fact that SPRIND remains an exception within the overall framework of German research funding.

The problem of bureaucracy is not an isolated phenomenon in the funding sector. Studies by the Institute for SME Research in Bonn document that small industrial SMEs are burdened so significantly by bureaucratic obligations that the costs can even exceed their average annual gross profit margin of 5.5 percent. For a small company with 150 employees and €35 million in annual revenue, the burden amounted to €2.18 million, which corresponds to 6.3 percent of revenue. This figure is roughly equivalent to the average salary of 34 full-time employees.

Research infrastructure and human capital as strategic resources

Germany invests substantial funds in research and development. According to preliminary calculations by the Federal Statistical Office, €129.7 billion flowed into this sector in 2023, representing a seven percent increase compared to the previous year. The share of expenditure in gross domestic product (GDP) remained at 3.1 percent, the same as the previous year. This means that the EU's Europe 2020 growth strategy target of spending at least three percent of GDP on research and development has been met for the sixth consecutive year. The German government is pursuing the ambitious goal of increasing this share to 3.5 percent by 2025.

The private sector traditionally bears the lion's share of these expenditures. In 2023, the business sector invested €88.7 billion, an increase of eight percent compared to the previous year. Spending on publicly funded non-university research institutions rose by six percent to €18.6 billion during the same period, while higher education spending increased by 1.8 percent to €22.4 billion. In 2024, German companies increased their spending on in-house research and development only slightly, by 2.3 percent, to a total of €92.5 billion, which is roughly in line with the inflation rate.

These investments flow into a research ecosystem of considerable depth and breadth. The cooperation between the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft and the Max Planck-Gesellschaft within the framework of the Pact for Research and Innovation represents an institutional bridge between applied and basic research. The Fraunhofer-Max Planck Cooperation Program selects scientifically outstanding projects for funding each year. This close collaboration is of strategic importance for technology transfer, as deep-tech innovations typically emerge from basic research and subsequently need to be further developed in an application-oriented manner.

Max Planck Innovation is responsible for technology transfer within the Max Planck Society. This organization supports the process when cutting-edge research forms the basis for innovative products and services that are implemented through licensing agreements or spin-off companies. The 4Investors Days regularly bring research startups together with investors, where teams from Fraunhofer, Helmholtz, Leibniz, and the Max Planck Society present their projects.

Paradoxically, a potential boost to the German research ecosystem could come from the United States. The policies of the current US administration have apparently triggered a so-called brain drain, prompting top scientists to emigrate. A survey published in the journal Nature revealed that 75 percent of the US scientists surveyed are considering leaving the country. This trend is particularly pronounced among early-career researchers: 80 percent of postdocs and 75 percent of doctoral candidates are actively seeking opportunities outside the US.

The president of the Max Planck Society anticipates an influx of US researchers to Germany. German scientists have proposed a recruitment program under the motto "100 Bright Minds for Germany," aimed at attracting top talent and strengthening Germany's position as a research hub. The proposed Meitner-Einstein Program could create up to 100 professorships for US scientists at risk of losing their jobs. Since the change of government, approximately 54 percent of German companies view the US as less attractive to top talent in business and academia.

Suitable for:

- A startup as intrapreneurship: Innovation from the inside out - New ways in market development - The Google 20% time model

The systemic capital gap as a brake on growth

The most serious structural deficit in the German innovation ecosystem lies in the area of growth financing. The increased research allowance, approved by the Bundestag's investment booster in June 2025, represents a politically sound and beneficial step for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The assessment basis has been raised to €12 million, having started at €2 million in 2020. SMEs receive 35 percent funding for their research expenditures, while larger companies receive 25 percent. The maximum funding can amount to up to €3.5 million annually for SMEs and up to €2.5 million for large companies.

These improvements, however, primarily address the research phase. The real problem lies with the medium-sized businesses of tomorrow: the startups in the scaling phase. Effective programs for initial financing do exist in Germany. The EXIST program celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2024 and has established itself as one of the most successful federal funding instruments for spin-offs from academia. Each year, EXIST supports the founding of approximately 250 high-tech startups and over 200 startup centers at universities. The 3,000th EXIST startup grant has already been awarded.

The High-Tech Gründerfonds (HTGF) is one of the most active early-stage investors in Germany and Europe. Since its founding in 2005, HTGF has financed more than 770 startups and achieved nearly 200 successful exits. With the launch of its fourth fund, HTGF has approximately €2 billion under management. External investors have invested around €5 billion in more than 2,000 follow-on financing rounds in the HTGF portfolio to date. The HTGF Opportunity Fund, launched in 2024 with a volume of €660 million, is designed to support selected companies in later growth phases with larger financing amounts of up to €30 million.

The DeepTech & Climate Fund finances high-growth deep-tech and climate-tech companies in Germany and Europe with investments of up to €30 million. The fund plans to invest up to €1 billion in the coming years and acts as a bridge between investors, SMEs, and innovative startups in the fields of climate, computing, industry, and life sciences.

Despite these instruments, significant scaling problems persist. When it comes to the second and third stages of financing—the growth phase, in which business models need to be scaled and substantial expansion financed with high risk of loss—the German market exhibits considerable weaknesses. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) refers to this as a scaling gap. The Future Fund, launched in 2021 with a total volume of €10 billion, addresses this issue but has not yet been able to close the fundamental financing gap. By the end of 2023, €3.3 billion from the fund had already been invested.

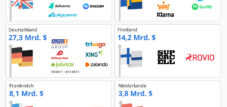

The scale of this gap becomes clear in international comparison. While around €7.4 billion was invested in startups in Germany in 2024, the venture capital volume, measured as a percentage of GDP, was only about 0.18 percent. The US averaged 0.85 percent between 2019 and 2024, and the UK 0.74 percent. The German market is thus more than three times smaller than the leading venture capital markets when measured as a percentage of GDP. In absolute terms, US investors invest six to eight times more venture capital in European companies each year than European investors.

The European Union raises only five percent of global venture capital, compared to 52 percent in the United States and 40 percent in China. Ten years after their founding, European scale-ups raise 50 percent less capital than their counterparts in San Francisco. This capital gap exists regardless of industry, founding year, or economic cycle.

Our EU and Germany expertise in business development, sales and marketing

Industry focus: B2B, digitalization (from AI to XR), mechanical engineering, logistics, renewable energies and industry

More about it here:

A topic hub with insights and expertise:

- Knowledge platform on the global and regional economy, innovation and industry-specific trends

- Collection of analyses, impulses and background information from our focus areas

- A place for expertise and information on current developments in business and technology

- Topic hub for companies that want to learn about markets, digitalization and industry innovations

From funding dreams to exodus: The strategic funding gap in the German startup ecosystem

The exodus paradox as a strategic failure

The consequences of this funding gap manifest themselves in a significant economic paradox. Despite government involvement, numerous promising industrial startups still cross the Atlantic. They do so not out of a fundamental aversion to Germany as a business location, but simply because the financing and thus growth opportunities are better in the USA.

This phenomenon exhibits a paradoxical dual structure that is highly problematic from an economic perspective. On the one hand, Germany spends taxpayers' money to promote promising startups. On the other hand, when these startups are ready to compete in the market, they are effectively released into the arms of foreign investors. Investors from the US and other countries benefit from German basic research and early-stage funding without having invested in these preliminary stages themselves.

The proportion of European tech companies relocating their headquarters outside the EU after a third funding round has already reached 30 percent, compared to 18 percent in previous years. This exodus of 30 percent of successful startups jeopardizes Europe's technological sovereignty and future value creation. In the US, approximately $146 billion flowed into AI startups alone in 2025, roughly ten times the European figure.

The situation is further complicated by current geopolitical developments. On the one hand, 70 percent of German founders consider the US, under the current administration, a risk to the German economy. More than a third would currently hesitate to collaborate with startups or companies from the US, and 87 percent demand that Germany strengthen its digital sovereignty to become more independent from the US. On the other hand, 31 percent of startups are re-evaluating potential funding from US investors, with 13 percent preferring EU investors due to the change in government.

The European level is responding to this challenge with its own initiatives. The European Investment Bank plans to provide around €70 billion for start-up and scale-up companies by 2027. The TechEU program aims to mobilize a total of €250 billion for the European technology sector. The European Commission is working with private investors on the Scale-up Europe Fund, a multi-billion-euro fund for investments in strategic deep-tech areas. This fund is set to launch with a volume of €5 billion and will continue to grow.

Suitable for:

- The Great Innovation Lie in Marketing: The Self-Destruction of an Industry? The Innovation Theater and Exploitation Trap

Technological priorities and strategic positioning

Germany's High-Tech Agenda focuses on six key technologies: artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, microelectronics, biotechnology, fusion and climate-neutral energy production, as well as technologies for climate-neutral mobility. This focus marks a departure from the decades-long "scattershot" approach, in which tens of billions of euros were distributed broadly among research institutes and companies. In the future, funds will be concentrated where Germany has particularly great opportunities and also a particularly high need.

In the field of artificial intelligence, the German government aims to increase labor productivity. By 2030, ten percent of economic output is to be generated using AI. For 45.1 percent of German startups, AI is already a core component of their product. The German government plans to attract at least one of the European AI Gigafactories to Germany. Around three billion euros are expected to flow into German AI startups in 2025, one billion more than in the previous year.

AI-based robotics presents a unique opportunity for Germany. Baden-Württemberg is a leader in robotics technology in Germany, particularly in industrial robotics. The headquarters of approximately one-third of Germany's top 50 robot manufacturers are located in this state. The combination of AI and robotics enables intelligent robots that can react autonomously and flexibly to changing production conditions. Around one-fifth of German industrial companies already use AI robotics, and another 42 percent are planning to implement it.

Germany holds a strong international position in quantum technology research, a position it intends to maintain. With funding commitments exceeding US$5.2 billion by 2026, the German government is planning, among other things, the construction of a universal quantum computer. The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Quantum Technologies. A planned EU quantum law, expected to be adopted in 2026, aims to promote research and innovation, expand industrial capacity, and strengthen supply chain resilience and governance.

Strategic decisions were also made in the field of biotechnology. A National Strategy for gene- and cell-based therapies was presented to the Federal Minister of Education and Research in June 2024. The Berlin Institute of Health at Charité was tasked with promoting projects for the development of gene- and cell-based therapies and related diagnostics. The aim is to accelerate the transformation of innovative therapies into marketable and clinically applicable products and to strengthen the network between research institutions and industry.

Suitable for:

Institutional reforms and freedom of innovation

The German government has recognized that institutional reforms are necessary to accelerate innovation. The planned Innovation Freedom Act aims to reduce bureaucratic hurdles in research funding, create a more innovation-friendly environment, and strengthen Germany's position in international competition. Research funding should thus become simpler, faster, and more digital.

At the launch event for the High-Tech Agenda, the Fraunhofer Society emphasized that knowledge transfer requires freedom. A legal framework is needed that creates the necessary freedoms and flexibility for a modern and efficient transfer of knowledge. The digitalization of project funding within the project funding information system is intended to make the entire process faster, more transparent, and more user-friendly. Through the integration of digital identity, the incorporation of AI tools, and the modernization of the technical infrastructure, a user-oriented federal funding management system is to be created.

The Academic Freedom Act provides for a more flexible approach to the prohibition of preferential treatment for non-profit research institutions, which should result in fewer individual applications needing to be submitted and reviewed in the future. The Research Data Act aims to create clear and practical legal frameworks so that public sector data can be used more easily for research purposes.

In its 2025 annual report, the Expert Commission on Research and Innovation (EFI) underscored the need for a more effective research and innovation policy. Germany's weak economic performance is also limiting its competitiveness. The EFI advocates for significantly more investment and a framework that enables greater impact. Without a long-term future strategy, industrial policy will remain piecemeal.

Suitable for:

Technological sovereignty in the context of global dependencies

The question of technological sovereignty is gaining increasing importance in light of geopolitical shifts. Europe faces a dual dependency: on information infrastructure on the one hand, and on trade in digital technologies on the other. For laptops and smartphones, Europe relies on Asian manufacturers, while in artificial intelligence, US giants dominate. While Germany and the European Union are becoming increasingly dependent on others in digital matters, the USA, China, and South Korea have been able to expand their digital autonomy.

A study by the University of Bonn has developed a Digital Dependency Index, which shows that the gap with the USA is widening. While Germany still possesses comparatively large ICT capacities and strong research institutions, the federal government's high-tech strategy has so far remained a vague collection of declarations of intent and has failed to achieve the necessary integration of research, industry, and infrastructure.

The German government aims to strengthen the economy and create new jobs through investments in key technologies, while also ensuring Germany's greater independence. At the launch event for the High-Tech Agenda, Chancellor Friedrich Merz emphasized that economic and research policy must not allow the USA and China to solely determine the technological future. This, he stated, is crucial for prosperity, security, and freedom.

The coalition agreement envisions the establishment of a Germany Fund, designed to combine the power of private financial markets with the long-term strategic approach of the state as an investor. At least ten billion euros of federal equity capital will be provided through guarantees or financial transactions. Private investments and guarantees will leverage this capital to at least 100 billion euros. The Future Fund is to be made permanent beyond 2030, with the goal of increasing investments from the WIN initiative to over 25 billion euros. A second Future Fund, with a strong focus on spin-offs and growth in deep tech and biotech, is intended to improve the entrepreneurial culture at universities and research institutions.

The WIN initiative, which aims to mobilize growth and innovation capital for Germany, has secured commitments from banks, insurance companies, and industrial enterprises. The goal is to establish five to ten excellence-oriented startup factories that will foster innovative and science-based spin-offs. These institutional decisions signal a growing political awareness of the strategic importance of innovation financing.

Regional disparities and ecosystem dynamics

The German startup landscape exhibits significant regional differences. Berlin accounts for the largest share at 18.8 percent, closely followed by North Rhine-Westphalia at 18.7 percent and Bavaria at 15.0 percent, with Munich, as an important center, contributing 7.5 percent. The four federal states of Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, Baden-Württemberg, and Saxony dominate the application and approval statistics for the EXIST programs.

Nearly a third of founders see their company as a deep-tech startup. The German Startup Monitor 2025 shows that research, knowledge transfer, and technological excellence are becoming crucial drivers. The AI startup landscape in 2025 comprises 935 startups, representing a 36 percent increase compared to the previous year. A third of AI startups in Germany are university-based and research-oriented, which offers significant potential for transferring cutting-edge research into practical applications.

A remarkable trend is emerging in the DefenseTech sector. In 2025, nearly €900 million flowed into this area, twice as much capital as in the entire previous year. 1.7 percent of startups target military customers, while another 24.1 percent develop dual-use products. The High-Tech Agenda explicitly identifies security and defense research as one of the strategic research areas in which investment is to be made.

However, the dynamics of cooperation between startups and established companies show a worrying trend. Only 56 percent of startups now collaborate with established companies, representing a significant decline and diminishing growth opportunities. This decreasing intensity of cooperation is problematic because the combination of startup agility with industrial scaling expertise is crucial for deep tech success.

The willingness to start a business is also showing critical trends. While 78.3 percent of founders express the desire to start another business, this is a significant decline compared to almost 90 percent two years ago. Furthermore, 28.5 percent of potential founders are considering starting a business abroad. These figures signal a certain disillusionment with the conditions in Germany.

Perspectives for a strategic realignment

The analysis of the German deep-tech landscape reveals a complex tension between existing strengths and systemic weaknesses. Germany boasts excellent basic research, a strong industrial base, and an internationally recognized engineering culture. However, these advantages must be more consistently focused on technologies that will shape the markets of tomorrow.

The need for action extends across several dimensions. First, funding processes must be radically accelerated. SPRIND's experience shows that agile funding structures are possible and lead to measurable success. Second, the scaling gap in growth financing must be closed. The promised instruments, such as the Germany Fund and the Future Fund II, must be operationalized quickly. Third, closer collaboration between research, industry, and politics is needed to make technology transfer and scaling more effective.

The High-Tech Agenda, with its focus on six key technologies and the end of a scattershot approach to funding, points in the right direction. Chancellor Merz has declared innovation policy the highest priority of the Federal Government. Concrete measures are being initiated with the action plan for nuclear fusion, the national microelectronics strategy, and the planned funding initiatives for next-generation AI models.

The success of these measures will depend on significantly shortening the time between political announcement and tangible impact. Technologies like AI are developing so rapidly that traditionally sluggish project funding approaches cannot keep pace. It must be easier to make adjustments to ongoing funding projects and to take into account the interim progress of technological development.

The international competitive landscape allows no delay. Increased investment in research and development will lead to a significant long-term increase in gross domestic product. Those who fail to master the key technologies of the future will be dominated by them. Without its own expertise, Germany will lose not only prosperity but also security.

The German government has recognized the strategic importance of innovation. Now, consistent implementation is crucial. Germany doesn't need to do everything itself or master every key technology in detail. What it needs are globally unique capabilities in selected technology fields to respond appropriately to the changing geopolitical landscape. The coming years will show whether this understanding can be translated into sustainable innovation successes, or whether Germany will continue to leave its technological lead to others in the final stretch.

Your global marketing and business development partner

☑️ Our business language is English or German

☑️ NEW: Correspondence in your national language!

I would be happy to serve you and my team as a personal advisor.

You can contact me by filling out the contact form or simply call me on +49 89 89 674 804 (Munich) . My email address is: wolfenstein ∂ xpert.digital

I'm looking forward to our joint project.

☑️ SME support in strategy, consulting, planning and implementation

☑️ Creation or realignment of the digital strategy and digitalization

☑️ Expansion and optimization of international sales processes

☑️ Global & Digital B2B trading platforms

☑️ Pioneer Business Development / Marketing / PR / Trade Fairs

🎯🎯🎯 Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, five-fold expertise in a comprehensive service package | BD, R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization

Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, fivefold expertise in a comprehensive service package | R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization - Image: Xpert.Digital

Xpert.Digital has in-depth knowledge of various industries. This allows us to develop tailor-made strategies that are tailored precisely to the requirements and challenges of your specific market segment. By continually analyzing market trends and following industry developments, we can act with foresight and offer innovative solutions. Through the combination of experience and knowledge, we generate added value and give our customers a decisive competitive advantage.

More about it here: