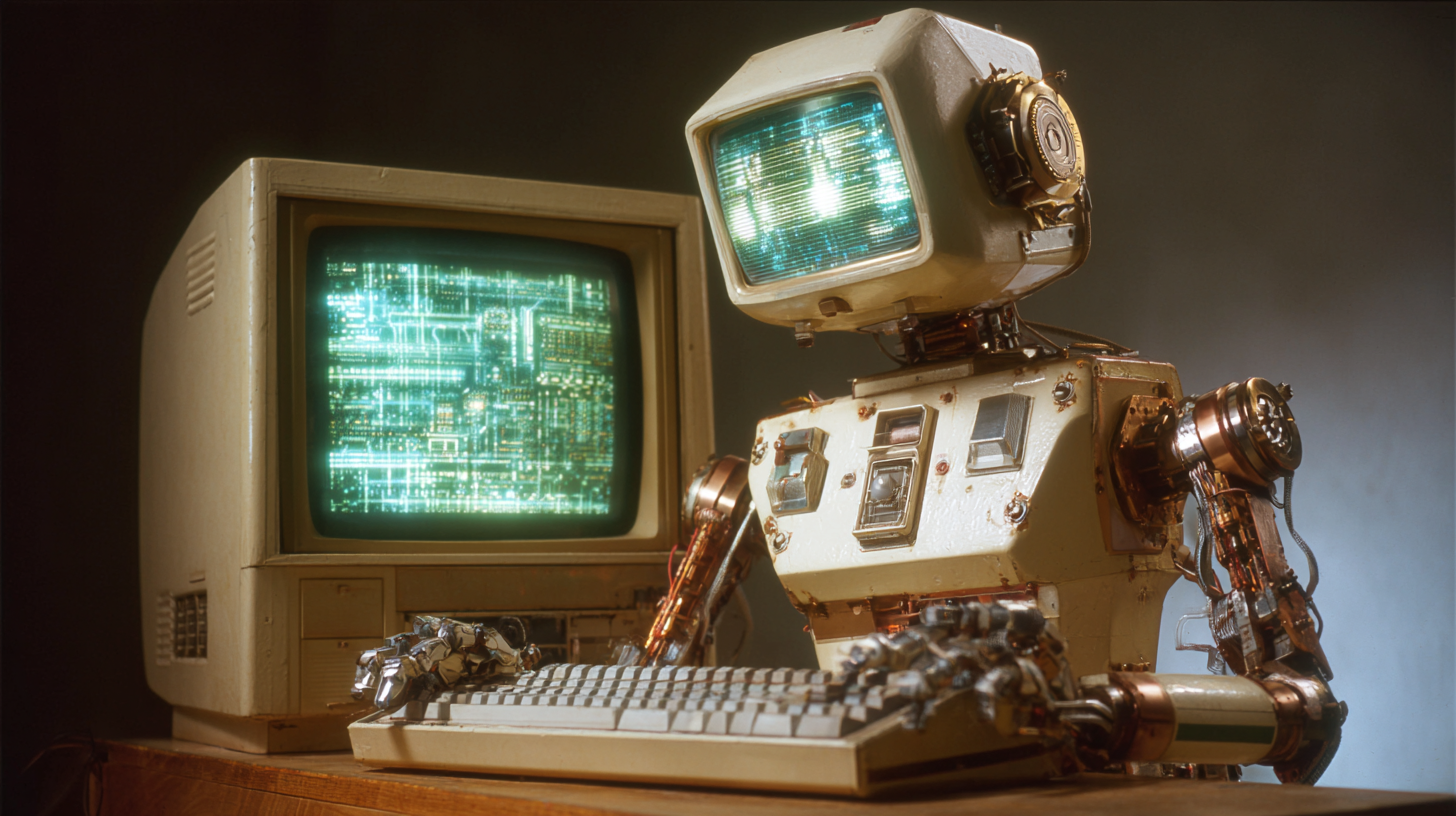

Computers in 1978, now AI and robotics: progress makes people unemployed – why this 200-year-old prophecy keeps failing – Image: Xpert.Digital

No mass unemployment due to AI: Why Germany faces a completely different problem

The fear of the “end of work”: A historical misconception and the opportunities of the new technological wave

Since the dawn of industrialization, a gloomy narrative has shadowed human progress: the fear that machines will render humans obsolete. Whether it was the mechanical looms of the 18th century that drove disaffected workers to revolt, or the microelectronics debate of the 1970s, which, under the slogan "progress makes you unemployed," prophesied a social catastrophe—the pattern is always the same. Today, in the age of artificial intelligence and humanoid robots, we are witnessing a resurgence of these fears. But a deeper look at economic history and current labor market data reveals that the panic surrounding technological mass unemployment is not only historically unfounded, it also fails to recognize the fundamental demographic challenges of our time.

Historical evidence paints a completely different picture than the apocalyptic visions of past decades. Despite massive upheavals—from the steam engine to the computer—work has not disappeared. It has transformed. The so-called "compensation thesis" has proven robust: Where old job profiles vanished, entirely new industries and fields of activity emerged due to productivity gains and new needs. In fact, more people are employed in Germany today than ever before, and 60 percent of today's workers perform jobs that didn't even exist 80 years ago.

The current debate differs from all previous ones in one crucial aspect: the demographic factor. While we discuss whether AI will replace us, Germany is heading towards a shortage of five million skilled workers by 2030. In this light, automation and robotics no longer appear as a threat, but as necessary allies for securing prosperity and relieving human labor of dangerous or monotonous tasks.

This article analyzes the cycles of technology anxiety, highlights the empirical facts of structural change, and ventures a look at why the AI revolution does not mean the end of work, but could mark the beginning of a new, more humane working world.

Suitable for:

The eternal prophecy of the end of work: Why every technological revolution awakens the same fears and why they always prove to be unfounded.

The history of human labor is inextricably linked to the history of technological upheaval. From the first mechanical looms in 18th-century England to the humanoid robots and artificial intelligence systems of today, a persistent refrain has accompanied technological progress: the fear of the end of human labor. This fear is as old as industrialization itself and recurs with remarkable regularity with each new technological wave. Yet historical evidence paints a different picture than the bleak scenario of mass unemployment. Work has changed; it has been transformed, redefined, and redirected in entirely new directions, but it has not been abolished.

The 1978 Spiegel cover, headlined "The Computer Revolution" and subtitled "Progress Makes You Unemployed," exemplifies this cyclical fear of technology. The magazine depicted a robot carrying a worker away from his workplace in a factory, an image that captured the collective anxieties of an entire generation. Almost forty years later, in 2016, the same magazine published a strikingly similar cover: "You're Dismissed," addressing the question of how computers and robots are taking our jobs and which professions will still be secure tomorrow. The visual language was nearly identical; only the protagonists had changed: instead of the factory worker, a businessman was now being removed from his office. This parallel is no coincidence, but rather an expression of a deeply rooted human reaction to technological change.

Analyzing these historical patterns reveals a fundamental truth about the relationship between technology and labor: technological progress does not inherently lead to less work, but rather to a redistribution of jobs and the workforce. This insight, confirmed by labor market researchers at the Institute for Employment Research, is key to understanding past, present, and future technological transformations.

The microelectronics debate and its apocalyptic visions

The late 1970s marked a turning point in the German technology debate. Microelectronics, described by DGB (German Trade Union Confederation) chairman Heinz Oskar Vetter as the third technological revolution, triggered a wave of existential anxiety among trade unionists and workers. Karl-Heinz Janzen, executive board member of the IG Metall (Metalworkers' Union), the world's largest single trade union, predicted a social catastrophe if no solution was found. In Reutlingen, 1,300 IG Metall officials displayed banners expressing their view: "We will not be sacrificed on the altar of progress; it's almost too late."

The trade union magazine Metall, with a circulation of 2.6 million, warned of job killers and accused industry radicals of undermining all efforts to achieve full employment. British trade union leader Clive Jenkins expressed this fear in stark terms: computers could replace most people's jobs for most of the time. This, he said, was not science fiction, but a realistic assumption for the turn of the millennium.

These predictions didn't seem unfounded at the time. Case studies of individual industries appeared to confirm the gloomy forecasts. In the German watchmaking industry, predominantly located in the Black Forest, workers experienced the full force of technological change. At the beginning of the 1970s, the industry still employed almost 32,000 workers. Just a few years later, that number had plummeted to 18,000. The mechanical watch, with its approximately 1,000 operating steps, was replaced by chronometers of a new era, assembled from only five parts: battery, quartz crystal, digital display, electronic circuitry, and case.

Similar developments were observed in other industries. When the SEL Group converted its teletype machine production to electronics, manufacturing time was reduced from over 75 hours to just under eleven hours. The old teletype machine consisted of 936 individual parts, some of which were manufactured on-site; the new model contained only one purchased component the size of a postage stamp. The consequences were soon reflected in the payroll: 160 SEL employees received termination notices, and 150 skilled workers were demoted by up to five pay grades.

From Weberian revolts to computer anxiety: The persistence of arguments

An examination of automation discourses from the 18th century to the present reveals a remarkable continuity in argumentative patterns. Already in the context of the so-called Machine Break, when disgruntled weavers and spinners in England and Germany revolted against mechanical looms and spinning machines, the same fears were articulated that characterize today's debate on artificial intelligence and humanoid robots.

The Industrial Revolution, which began in England in the second half of the 18th century, triggered the first major wave of technological unemployment anxieties. The Spinning Jenny, a loom invented in 1765 that could process multiple threads simultaneously, was perceived as the beginning of the struggle between machine and man in production chains and factory halls. On August 28, 1830, in Kent, a small town on the road from Dover to London, hundreds of wage laborers and day workers, armed with pitchforks, axes, hammers, and sticks, stormed threshing machines that were taking their jobs. These uprisings, known as the Swing Riots, spread throughout England in the following weeks.

The Silesian weavers' uprising of 1844 is considered the most famous German case of machine-breaking. On June 3, 1844, about 20 weavers from Peterswaldau and surrounding villages met on Kapellenberg hill and discussed how to resist the factory owners. They then marched, singing the satirical song "Blutgericht" (Blood Court), to the factory of the Zwanziger brothers, who were publishers and had cut wages. These early protests were an expression of an existential fear that would recur in every period of technological upheaval.

The automation debate of the 1950s seamlessly continued this tradition. The development of computers and the associated concept of an electronic brain, closely linked to cybernetics as the science of control and regulation, triggered a new debate on automation. The cyberneticist Norbert Wiener painted a dramatic picture, warning that the problem of unemployment as the price of automation was a very significant challenge facing modern society.

The discourse was consistently characterized by a polarization that persists to this day. While companies, management, and engineers tended to emphasize the advantages of automation and its necessity for prosperity and progress, the arguments of sociologists, the media, and trade unions focused far more on the dangers of automation, especially the disappearance of jobs, the replacement of humans, and potential deskilling processes.

The demographic imperative and the new significance of automation

The current debate surrounding robotics and artificial intelligence differs from all previous technological upheavals in one crucial aspect: the demographic context. Germany and other developed economies are facing an unprecedented labor shortage, which casts the entire discussion about technological unemployment in a new light.

The German Economic Institute (IW) predicts that Germany will face a shortage of five million skilled workers by 2030. The main reason lies in demographic trends: the baby boomers are retiring, while significantly fewer young people are entering the workforce. In 2022 alone, over 300,000 more people retired than entered the workforce. This trend is expected to peak in 2029, when the particularly large birth cohort of 1964, comprising 1.4 million people, reaches retirement age. This contrasts sharply with only about 736,000 potential new entrants to the workforce from the 2009 birth cohort – a gap of 670,000 workers this year alone.

This demographic reality is fundamentally changing the perspective on automation. Robots and AI systems are no longer primarily perceived as a threat, but rather as a necessary complement to a shrinking workforce. The automatica Trendindex 2025, for which 5,000 employees in five countries were surveyed, clearly illustrates this shift in perception: 77 percent of Germans support the use of robots in factories. Three-quarters are convinced that robotics will counteract the shortage of skilled workers. Around 80 percent would like robots to take over dangerous, hazardous, or repetitive tasks.

The acceptance of robots is clearly present, and the majority of employees recognize that automation is a good measure to relieve the burden on workers and counteract the labor shortage. 85 percent of those surveyed believe that robots reduce the risk of injury during hazardous tasks. 84 percent see robots as an important solution for handling critical materials. Around 70 percent believe that robots could help older people remain in the workforce longer.

Sectoral structural change as a historical constant

To understand the impact of technological disruptions on the labor market, it is essential to examine long-term sectoral structural change. The development of employment shares in the three economic sectors reveals one of the most profound transformations in economic history.

In 1950, 24.6 percent of the workforce in West Germany was employed in agriculture, forestry, and fishing. By 2024, this figure had fallen to approximately 1.2 percent. Simultaneously, the share of those employed in the service sector rose from 32.5 percent to 75.5 percent. This shift represents the loss of millions of agricultural jobs, but it was accompanied by the creation of numerous new employment opportunities in the industrial and, later, the service sector.

Despite massive technological upheavals, the number of employed people in Germany has risen steadily over the long term. From 1970 to 2024, the number of employed people increased from approximately 38 million to over 46 million, a rise of more than 18 percent. This development impressively refutes the recurring predictions of mass unemployment due to technological change.

Technological progress in Germany has not so far led to less work, but rather to a redistribution of jobs and the workforce. For highly skilled workers, more jobs have been created than have disappeared. Conversely, for low-skilled workers, fewer jobs have been created than have been lost. Technological development has thus been linked to a qualitative change in the demand for labor: the demand for highly skilled workers has increased, while the demand for low-skilled workers has decreased.

The empirical evidence for the compensation thesis, or more simply: Why digitalization still creates jobs

The so-called compensation thesis has always been put forward against the dire predictions of the end of the work society: Disappearing jobs are compensated for by newly created ones, and therefore there can be no talk of the end of the work society. Empirical research over the last few decades has largely confirmed this thesis.

A study by the Institute for the Future of Work and the Centre for European Economic Research shows that automation ultimately created 1.5 million additional jobs in Europe over the past decade. While machines did cost Europe 1.6 million jobs between 1999 and 2010, particularly in manufacturing, the original plans of companies indicated that this number would have been three times higher. However, computers and robots enabled cheaper production of goods. As a result, consumers bought more, creating new jobs. This resulted in a net gain of three million jobs, twice the number eliminated by the machines.

The Institute for Employment Research (IAB) arrives at similar conclusions. Computerization over the past 20 years has not increased the proportion of jobs lost. Since 2005, it has even declined. Therefore, there is no trend toward a turbocharged labor market, because then the rates of job creation and loss would have to increase.

Regarding the digitalization debate, the IAB predicts that, once again, the overall employment level in Germany will not decline. By 2040, approximately 4.0 million jobs will be lost compared to 2023, while 3.1 million new jobs will be created. The net effect of digitalization on overall employment is therefore expected to be positive.

The World Economic Forum's Future of Jobs Report 2025 confirms this trend on a global scale. The report forecasts that by 2030, 22 percent of current jobs worldwide will either be created or eliminated through structural changes. This includes the creation of jobs amounting to 14 percent of today's total employment, which equates to approximately 170 million new jobs. At the same time, it is expected that 8 percent of current jobs, around 92 million, will be lost. Overall, this results in a net increase of 7 percent in total employment, which corresponds to approximately 78 million new jobs.

Our global industry and economic expertise in business development, sales and marketing

Our global industry and business expertise in business development, sales and marketing - Image: Xpert.Digital

Industry focus: B2B, digitalization (from AI to XR), mechanical engineering, logistics, renewable energies and industry

More about it here:

A topic hub with insights and expertise:

- Knowledge platform on the global and regional economy, innovation and industry-specific trends

- Collection of analyses, impulses and background information from our focus areas

- A place for expertise and information on current developments in business and technology

- Topic hub for companies that want to learn about markets, digitalization and industry innovations

AI, robotics and new jobs – further training instead of job loss: How companies are preparing their workforce for the AI revolution

The emergence of new professions and industries

Every technological revolution has not only transformed existing jobs but also given rise to entirely new professions and entire industries. This creative dimension of technological change is often overlooked in public debate, as attention focuses on the visible losses, while the emerging opportunities only become apparent in retrospect.

In fact, 60 percent of today's workforce is employed in jobs that didn't even exist 80 years ago. Digital transformation is continuously creating new job profiles, many of which couldn't have been conceived just a few years ago: AI developers create the algorithms that are used across industries. Data scientists analyze vast amounts of data to gain valuable insights. AI ethics consultants ensure the ethically responsible development and application of AI systems. Robot trainers teach robots and machines to perform specific tasks.

The Future of Jobs Report 2025 identifies the fastest-growing professional fields: AI and machine learning specialists, big data specialists, process automation experts, information security analysts, software and application developers, and robotics engineers are at the forefront of growth. At the same time, demand is rising for professions based on strong human skills: sales and marketing professionals, human resources and corporate culture specialists, organizational development experts, innovation managers, and customer service representatives.

Another rapidly growing sector is the green economy. Professions such as renewable energy engineers, solar energy engineers, and sustainability managers are experiencing strong growth. The education and care sectors are also developing robustly: professions such as doctors, nurses, and teachers are expected to increase, driven by demographic trends such as the aging population and the fact that these jobs are difficult to automate.

Suitable for:

The limits of artificial intelligence and the irreplaceability of human abilities

The current debate surrounding generative AI and humanoid robots raises the fundamental question of which human skills can be replaced by technology and which cannot. Analyzing this boundary reveals why certain tasks will remain permanently in human hands.

While generative AI cannot replace human creativity, it is a powerful tool that can enhance the creative process. The weakness of generative AI lies in its inability to draw on subjective experiences and emotions. It lacks the personal perspectives and emotional nuances that make human works authentic and meaningful. Generative AI can mimic artists, but not replace them, because it lacks the depth and authenticity that human-created works possess.

Richard David Precht argues that, in the long run, technology will relieve humans of many routine tasks that do not require human qualities. Only those professions that society deems should continue to be performed by humans, such as childcare workers, teachers, and general practitioners, will remain unaffected by this development in the long term. This perspective emphasizes the social and emotional dimension of work, which extends beyond mere functionality.

The technological exposure of a job to AI says nothing about whether jobs will actually disappear or whether they will transform. AI can replace existing jobs, but it can also support them by making human work more productive or opening up entirely new fields of activity. As in previous waves of technological change, AI leads to shifts in power in the labor market, between occupational groups, between newcomers and experienced workers, and between employees and employers.

What is particularly noteworthy is that, according to recent studies, AI primarily affects highly skilled workers, representing a break with previous technological developments. While computerization mainly displaced routine tasks and thus contributed to the erosion of the middle class, AI could make specialized expertise more broadly available. By combining information, rules, and experience in ways that support sophisticated decision-making processes, it can enable employees with less formal training to take on tasks that were previously reserved for highly skilled experts.

Humanoid robots as an answer to the skilled worker shortage

The development of humanoid robots has accelerated remarkably in recent years. Between 2023 and 2025, the capabilities of humanoid robots, particularly in terms of speed, precision, and application areas, improved by 35 to 40 percent. Studies predict that 20 million humanoid robots will be in use by 2030, primarily in industrial applications.

This development should be understood primarily as a reaction to structural labor market problems, not as a replacement for human labor. According to estimates by Goldman Sachs Research, the market for humanoid robots could grow to a volume of US$150 billion by 2035. A key driver is the demographic-related shortage of skilled workers, which is already posing challenges for many industries.

Humanoid systems can be integrated into roles currently held by humans, such as logistics, assembly, or caregiving. They operate efficiently and do not require specially adapted infrastructure. In the first wave, humanoid robots can primarily handle logistical tasks like sorting, transporting, and providing goods, or inserting parts into machines. In the second wave, from 2028 to 2030, it is expected that humanoid robots will also be able to perform tasks with high variability, complex processes, and motor skills in assembly.

The economic advantages are considerable: pilot projects have shown increases in process efficiency of up to 350 percent and quality improvements of over 90 percent. These efficiency gains are primarily due to the fact that the robots can be used around the clock, 365 days a year. Furthermore, the humanoid robots can completely eliminate human error.

However, experts caution against overly optimistic expectations. A study by the Fraunhofer IPA shows that there is a long way between hype and reality. The human anatomy is unsuitable for many industrial applications, and the current performance of humanoid robots falls far short of specialized systems. Furthermore, there is a lack of legal frameworks and economically viable application scenarios. Only about 40 percent of those surveyed consider human-like hands or legs even necessary.

Changing qualification requirements

Technological disruptions are not only changing the number of jobs, but above all, their qualification requirements. Employees with AI skills are benefiting from a remarkable wage increase, which is projected to reach 56 percent globally in 2024, double the 25 percent increase of the previous year. The qualifications employers are seeking are changing 66 percent faster in jobs most affected by AI than in those least affected.

Productivity growth has quadrupled since the widespread adoption of GenAI in 2022 in the industries most impacted by AI. A key finding is that AI makes workers more valuable, more productive, and enables them to earn higher salaries, with job creation even increasing in sectors considered most susceptible to automation. This data suggests that companies are primarily using artificial intelligence to empower employees to create added value with the technology, rather than simply reducing the number of jobs.

The OECD warns, however, of growing polarization: In Germany, 18.4 percent of jobs could fall victim to automation, which is above the OECD average of 14 percent. Additionally, across the OECD, almost one in three jobs is likely to be significantly altered by digital technology. In Germany, this figure is even higher, at 36 percent. Only 50 percent of employees are adequately qualified and prepared for this transformation. The gap in continuing education between highly and low-skilled adults is the largest in the OECD in Germany.

The solution lies in massive investments in education and training. Policymakers must make continuing education a top priority. Low-skilled workers are at greater risk of losing their jobs, while highly skilled workers have better access to continuing education and are therefore much more likely to benefit.

Liberation from the burden of monotonous and dangerous work

One aspect of the technological revolution is often overlooked in public debate: the liberation of people from monotonous, dangerous, and physically demanding work. This emancipatory dimension of automation was already a central argument of proponents of technological progress in the 1970s.

The Japanese company Matsushita advertised its automated factories with the promise that workers who had to perform mindless routine tasks were now free to take on more interesting, productive, and rewarding jobs. This promise was fulfilled in many areas, even if the transition wasn't always smooth.

Current surveys confirm that employees share this perspective. 85 percent of respondents believe that robots reduce the risk of injury during hazardous activities. 84 percent see advantages in handling dangerous materials. 80 percent would like robots to take over dangerous or monotonous tasks.

The ROBDEKON research project, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, is developing robotic systems for decontamination in hazardous environments. Whether in nuclear facilities or in the disposal of contaminated sites, there are many workplaces where people are exposed to significant health risks. Research into such systems promises to free people from work environments that pose a danger to their health and lives.

The task of shaping politics, economy and society

The analysis shows that technological change is not a deterministic force to which society is passively subjected. Its effects are determined by the complex interplay in which changing technological conditions are absorbed by the labor market, the economy, society, and politics. This is where the opportunity lies to actively manage the technological transformation of the labor market.

Germany has taken important steps with the introduction of continuing education benefits and the expansion of training opportunities. However, these measures must be expanded and systematically integrated with labor market policy, the education system, and economic development. The 5.4 million recipients of the citizen's income allowance and the millions of people in precarious employment must be systematically retrained for future-oriented professions.

Companies that proactively shape change can not only survive but emerge stronger from the transformation. A medium-sized mechanical engineering company with approximately 350 employees invested in a comprehensive training program instead of cutting jobs. Within three years, the company succeeded in increasing its revenue by 40 percent while maintaining a stable workforce. The investment in training amounted to approximately €2,500 per employee per year and had already paid for itself after 18 months.

The key insight is this: Transformation is not optional, and it rewards not those who wait, but those who act proactively. Technology does not replace people, but rather enhances their capabilities when the right framework is in place.

The next technological revolution as a design opportunity

The history of technological revolutions teaches us that every wave of progress has been accompanied by the same fears, and that these fears have invariably proven to be exaggerated. The computer revolution of the 1970s fundamentally changed the world of work, but it did not eliminate it. The digitization of recent decades has transformed millions of jobs, but ultimately created more than it destroyed. There is no rational reason to assume that the current revolution driven by artificial intelligence and humanoid robots will be any different.

The humanoid robots and AI systems of the future will take work off our hands, but above all, they will take away monotonous, dangerous, and physically demanding jobs. Eighty percent of German employees want exactly that. Technology will free people from tasks that harm their health and stifle their creativity.

What remains are the genuinely human abilities: creativity based on subjective experiences and emotional depth; ethical judgment that machines cannot possess; the capacity for innovation and visionary thinking that goes beyond the reproduction of the known; and social and emotional skills that are indispensable in caregiving, education, and leadership.

The next technological revolution is knocking at the door. The question is not whether it will come, but how it will be shaped. Historical evidence shows that societies that actively embrace technological upheavals and prepare their people for change emerge stronger from these transformations. The fear of the end of work is as old as technological progress itself, and it has consistently proven unfounded. Work has not been abolished; it has been transformed, and with each transformation, new professions, new industries, and new opportunities for human development have emerged.

EU/DE Data Security | Integration of an independent and cross-data source AI platform for all business needs

Ki-Gamechanger: The most flexible AI platform-tailor-made solutions that reduce costs, improve their decisions and increase efficiency

Independent AI platform: Integrates all relevant company data sources

- Fast AI integration: tailor-made AI solutions for companies in hours or days instead of months

- Flexible infrastructure: cloud-based or hosting in your own data center (Germany, Europe, free choice of location)

- Highest data security: Use in law firms is the safe evidence

- Use across a wide variety of company data sources

- Choice of your own or various AI models (DE, EU, USA, CN)

More about it here:

Advice - planning - implementation

I would be happy to serve as your personal advisor.

contact me under Wolfenstein ∂ Xpert.digital

call me under +49 89 674 804 (Munich)

🎯🎯🎯 Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, five-fold expertise in a comprehensive service package | BD, R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization

Benefit from Xpert.Digital's extensive, fivefold expertise in a comprehensive service package | R&D, XR, PR & Digital Visibility Optimization - Image: Xpert.Digital

Xpert.Digital has in-depth knowledge of various industries. This allows us to develop tailor-made strategies that are tailored precisely to the requirements and challenges of your specific market segment. By continually analyzing market trends and following industry developments, we can act with foresight and offer innovative solutions. Through the combination of experience and knowledge, we generate added value and give our customers a decisive competitive advantage.

More about it here: