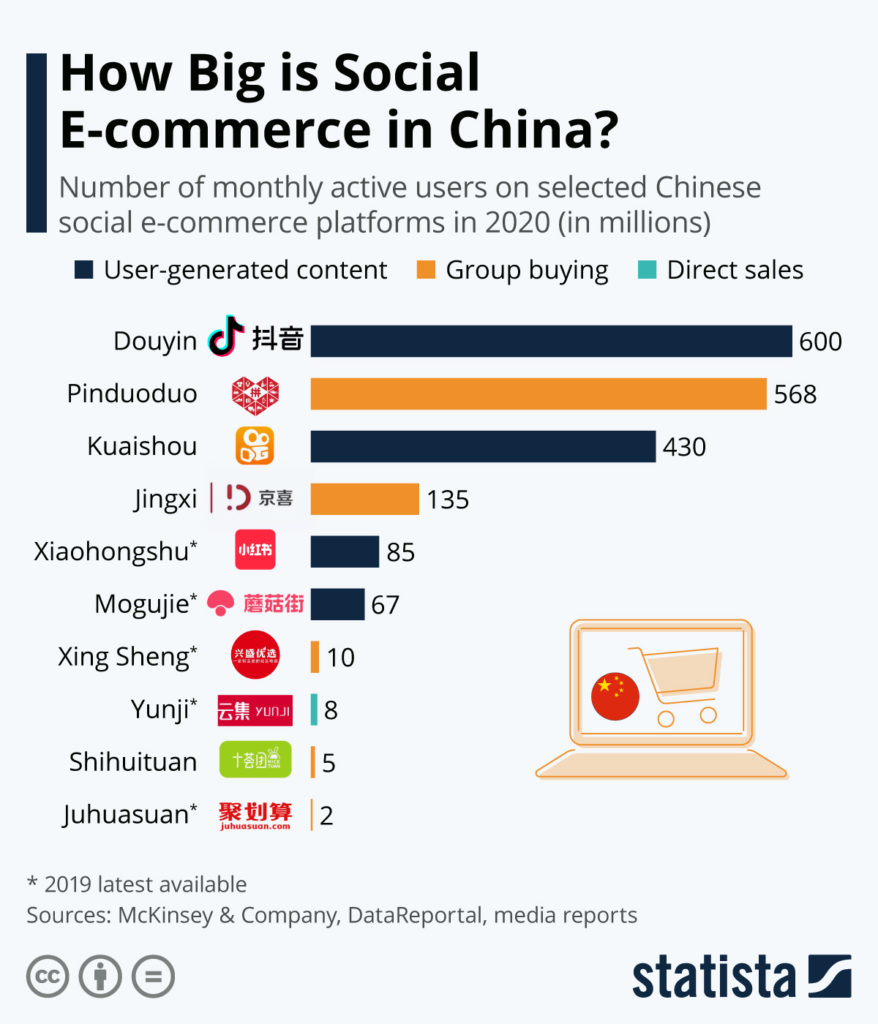

How big is social e-commerce in China?

Language selection 📢

Published on: April 30, 2021 / update from: April 30, 2021 - Author: Konrad Wolfenstein

How big is social e-commerce in China?

Social e-commerce in China is already a massive $300 billion market and will only grow in the coming years as a plethora of different services compete for the top positions in this sector. The graphic below shows some of the largest and most notable.

Some marketing concepts in Chinese social e-commerce are similar to those used by social media influencers in other countries (although they are a little flashier). Others are still almost unknown in North America or Europe.

When it comes to marketing products through user-generated content, Chinese social media apps have integrated the sales process. Douyin, the Chinese TikTok, may be very similar to its international counterpart as both belong to the same parent company, ByteDance. But Douyin has had its own in-app store , where users attracted by short videos can immediately purchase the products they see. Purchasing directly in the app or providing product descriptions that link to other e-commerce sites are both possible and certainly make tracking sales tied to influencers and content creators much easier. Kuaishou uses the same concept but focuses on smaller, less cosmopolitan cities, while Xiaohongshu and Mogujie focus more on pretty pictures (think Instagram with a shop) but are of course also full of influencers hawking their wares.

Nevertheless, many account holders on these user-generated content platforms may not be a buyer at all, but only viewers. With the rival concept Group Buying, on the other hand, users actually register with the intention of finding a deal together with their social network or people in their area. The monthly active users for Group Buying would of course be lower than in the platforms that concentrate on social media and e-commerce. An exception is Pingduoduo, a veteran of the Group Buying Concept, which had 568 million monthly users in the second quarter of 2020. Group Buying platforms offer prices that are increasingly cheaper the more articles a group buy. These “Groupon for War” apps typically also use Wechat's power, the massively popular Chinese Messenger and umbrella app so that people can address their friends and family. The apps are often platforms of third -party providers that connect wholesalers or even producers directly with customer groups and thus switch off more than one middleman to enable high discounts.

Chinese e-commerce giant JD, an inventory seller, launched its own group selling product Jingxi in 2019 with some success, using both its own logistics infrastructure and allowing third-party offerings. Alibaba's Juhuasuan isn't there yet, but it's also not allowed to be integrated into rival Tencent's WeChat app. Alibaba, which has always been a third-party platform, leveraged Juhuasuan and the group buying concept to overcome another frontier of e-commerce: fresh produce.

While low-cost, fast-moving goods still pose a challenge to e-commerce around the world, Chinese group buying has penetrated the market, albeit in smaller cities. Platforms that focus less on social contacts and more on neighborhood groups make it possible to use housewives or shopkeepers as contacts to send goods in bulk. It is then up to the neighborhood to distribute these, keeping last mile costs to a minimum. Xing Sheng, founded by a Hunan province grocery store chain, is beating Alibaba in the group grocery buying space, as is Beijing startup Shihuituan .

How Big is Social E-Commerce in China?

Social e-commerce in China is already a gigantic market of $300 billion, and it is poised to grow even more in the coming years as a plethora of different services vie for top positions in the sector. The chart below shows some of the largest and most noteworthy.

Some marketing concepts in Chinese social e-commerce are similar to those employed by social media influencers in other countries (while being a bit more on the nose). Others are still virtually unheard of in North America or Europe.

When it comes to marketing products via user-generated content, Chinese social media apps have integrated the sales process. Douyin, the Chinese TikTok, might be very similar to its international counterpart since both are owned by the same parent company, ByteDance. Yet, Douyin has had its own in-app store since 2018, where users lured in by short videos can instantly purchase the products they have viewed. Buying directly in the app or hosting product descriptions that link to other e-commerce sites are both possible and certainly make tracking sales tied to influencers and content creators a lot easier. Kuaishou employs the same concept while focusing on smaller, less cosmopolitan cities, while Xiaohongshu and Mogujie focus more on pretty pictures (think Instagram with a shop) but are, of course, also teeming with influencers peddling wares.

Yet, many account holders on these user-generated content platforms might not be buyers but just viewers. In rival concept group buying on the other hand, users actually log on with the intention to find a deal together with their social network or people living in their vicinity. Monthly active users for group buying would therefore be naturally lower than for those platforms focusing on social media and e-commerce. The exception is Pingduoduo, a veteran of the group-buying concept that boasted 568 million monthly active users as of Q2 of 2020. Group-buying platforms offer prices that get increasingly discounted the more items a group purchases. These “groupon for wares” apps typically also leverage the power of WeChat, the massively popular Chinese messenger and umbrella app, to let people approach their friends and family. Apps are often third-party platforms, connecting wholesalers or even producers directly with customer groups, cutting out more than one middle man in order to deliver steep discounts.

Chinese e-commerce giant JD, an inventory seller, launched its own group-selling product, Jingxi, with some success in 2019, leveraging its own logistics infrastructure as well as allowing third-party offers. Alibaba's Juhuasuan has not come as far yet but it is also not allowed to integrate on its rival Tencent's WeChat app. Alibaba, which has been a third-party platform all along, used Juhuasuan and the group buying concept to break down another frontier of e -commerce: fresh produce.

While low cost, fast-moving goods still pose challenges for e-commerce around the world, Chinese group buying has made inroads into the market, albeit in smaller cities. Focusing less on social contacts but on neighbor groups, platforms enable the use of stay-at-home mums or convenience store owners as points of contact to send goods in bulk. It is then up to the neighborhood to distribute them, keeping last-mile costs to a minimum. Xing Sheng, which was started by a grocery store chain from Hunan province, is beating Alibaba at the grocery group-buying game, as is Beijing startup Shihuituan .

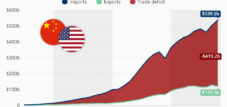

Conquering the Chinese market: data, figures, facts and statistics

China is not only the largest market in the world from e-commerce to social commerce, but also a big unknown in the Western world. The Chinese government provides massive support to the manufacturing industry, especially in the B2B sector. In 2019, 2/3 of e-commerce transactions in China alone came from the B2B market.

Conquering the China market: data, figures, facts and statistics – Picture: Poring Studio|Shutterstock.com

More about it here: