In vielen Industrieländern ist ein erheblicher Teil der Arbeitnehmer für ihren Arbeitsplatz überqualifiziert. Das Problem ist in den letzten Jahren immer häufiger aufgetreten, am deutlichsten in Volkswirtschaften mit wettbewerbsfähigen Arbeitsmärkten. Während es natürlich zu positiven Effekten für einige Unternehmen führen kann, wie z.B. die Bildung eines Mitarbeiters auf einem höheren Niveau, kann es auch zu höheren Gehaltsvorstellungen, einem niedrigeren Grad an Zufriedenheit und einer höheren Wahrscheinlichkeit führen, dass eine Person ihren Arbeitsplatz verlässt. Die OECD-Definition der Überqualifikationsquote ist der Anteil der Hochqualifizierten, die in einem Beruf arbeiten, der von der ISCO als gering oder mittelqualifiziert eingestuft wird.

Mehr als ein Drittel der hochqualifizierten Einwanderer in den OECD-Ländern sind für ihre Arbeit überqualifiziert, wobei die genaue Rate von Land zu Land sehr unterschiedlich ist. Mit Ausnahme von Portugal ist dieser Anteil in ganz Südeuropa besonders hoch, wo viele hoch qualifizierte Migranten niedrige und mittlere Qualifikationen haben. Dieses Gefälle wird nicht nur nach Südeuropa definiert, wie die folgende Infografik zeigt.

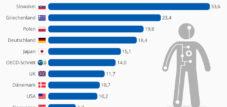

Griechenland (60,7 Prozent), Spanien (53,6 Prozent) und Italien (51,7 Prozent) sind bemerkenswerte Beispiele für südeuropäische Länder, in denen die im Ausland geborene Bevölkerung eine weitaus höhere Überqualifikationsquote aufweist als die einheimische Bevölkerung, deren Anteil 32 Prozent, 36,9 Prozent bzw. 16,9 Prozent beträgt. Südkorea hat den höchsten Anteil an Überqualifizierung unter den einheimischen Arbeitskräften, und noch interessanter ist, dass die im Ausland geborene Bevölkerung mit 74,5 Prozent einen noch höheren Anteil an Überqualifizierung hat. In den USA und Mexiko sind Einheimische und im Ausland geborene Arbeitnehmer gleichermaßen wahrscheinlich zu qualifiziert für ihre Arbeit.

In many developed countries, a considerable share of workers are overqualified for their jobs. The issue has become increasingly common in recent years, most evident in economies with competitive job markets. While it can of course result in positive effects for some organizations such as an employee peforming at a higher level, it can also result in higher salary expectations, a lower level of satisfaction and a higher chance of a person leaving their job. The OECD definition of the overqualification rate is the share of the highly educated who are working in a job that is ISCO-classified as low or medium skilled.

Over a third of highly educated immigrants in employment across OECD countries are overqualified for their jobs with the exact rate differing significantly between countries. Excluding Portugal, that share is particularly high across Southern Europe where many highly educated migrants are in low and medium-skilled jobs. That disparity isn’t just defined to Southern Europe as the following infographic shows.

Greece (60.7 percent), Spain (53.6 percent) and Italy (51.7 percent) are notable examples of Southern European countries where the foreign-born population has a far higher overqualification rate than the native-born population where the share is 32 percent, 36.9 percent and 16.9 percent respectively. South Korea has the highest share of overqualification among a native-born workforce and even more interestingly, its foreign-born population has an even greater share of overqualification at 74.5 percent. In the U.S. and Mexico, native and foreign-born workers are equally likely to be too skilled for their jobs.